Forget the Plot—Build Better One-Shots with Modular Encounters

I think writing One-shots for other people is HARD. I realize that my own structure for game prep is very unique and specific to the things I like to do as a Game Master. So…I’ve been trying lately to distill down what a One-Shot needs, and how can I make it universal for other GMs (mainly cause I’m creating a book currently).

A solid one-shot should strike the right balance between structured challenges and letting players get creative. Every encounter should give them interesting choices/options with real consequences. This can come from; multiple win conditions, dynamic environments, and a variety of encounter types. Hopefully this keeps players hooked.

Let’s dig into the tools that hopefully will help craft a one-shot that feels open-ended, immersive, and, most importantly, FUN.

What to Expect in this Newsletter?

The Philosophies of One-Shot design

Intro to One-Shot Design

Call to Action: Jumpstarting the Game

Non-Linear Encounters & Modular Play

Weaving Player Backstories into the Game

Varying Encounter Starting Positions

Designing EPIC Encounters

Expanding on Pressure in Encounters

Expanding on Interaction in Encounters

Drafting the Blueprint

Streamlining Assistance

Rewriting and Synthesizing Insights

How’s this Gonna Look?

Breaking Down a Book into Manageable Modules

Simplified One-Shot Information

Potential Example

Final Thoughts

Intro to One-Shot

When designing a one-shot for a tabletop RPG, it’s tempting to approach it like writing a short story or a screenplay—crafting a compelling plot with rising action, twists, and a big finale. And while a strong narrative can help, a rigid plot can sometimes work against the fluid, player-driven nature of TTRPGs.

The key is to strike a balance between structure and flexibility. A great one-shot doesn’t just push players through a set of predetermined story beats; it presents them with engaging challenges, each offering different paths to victory. Think of it as designing a puzzle box rather than a novel—players should be able to poke, prod, and twist different elements to uncover solutions. This approach keeps the game fast-paced and reactive, making every decision feel impactful.

By framing encounters around modular challenges rather than a fixed plotline, you create a one-shot that is open-ended, immersive, and tailored to player choice. Whether they’re navigating a deadly chase, unraveling a mystery, or breaking into a fortress, the focus shifts from following a script to engaging with the world in a meaningful way.

Call to Action

The idea of a Call to Action shows up everywhere - whether its the Hero’s Journey, storytelling in books, or even the Lazy Dungeon Master approach with its Fast Start concept. The key takeaway? You can’t waste too much time easing into the narrative - just go. Matt Colville has a great tip for when the pacing slows: “Orcs attack.” It’s a simple way to inject momentum, and the same principle applies to starting a game.

That said, I also love the idea of ritual. I saw a video once that talked about how Critical Role has a ritual at the start of every session - when Matthew Mercer delivers his intro, it follows the same cadence and rhythm every time. It’s a way of signaling to the players, “Okay, it’s game time.” You see the same concept in productivity science -people work better when they always use the same coffee shop or listen to the same playlist. Rituals have power.

Here are some example questions that Lazy Dungeon master says to use if you are trying to create a strong start:

What’s happening? What event will frame the start of this section of the adventure?

What’s the point? What seed or hook will lead the characters further into the adventure?

Where’s the action? Start as close to the action as you can.

When in doubt, start with combat.

The first two points focus on big-picture adventure design, but for a one-shot, it’s often better to start as close to the action as possible—when in doubt, open with combat. Sanderson emphasizes the need for motion, conflict, and change, while The Science of Storytelling highlights that people are drawn to unexpected shifts and incomplete information, sparking curiosity. You can create this intrigue by:

Presenting a question or puzzle

Introducing a sequence of events with an uncertain resolution

Setting up expectations that push players to search for an explanation

Establishing that key information exists but must be found or revealed

Non-Linear Encounters (Modules)

Instead of a rigid sequence of events, consider structuring one-shots in a modular format where players determine the order of encounters.

A great framework is a six-encounter structure, leading up to a climactic seventh encounter. Players decide how to navigate through them, meaning:

Some encounters may be skipped entirely.

Different groups may take different paths to the final showdown.

The order of challenges affects how players approach later encounters (e.g., they might weaken a boss by destroying its power source first).

This non-linear approach increases player agency, making each session feel unique.

Interweaving Player Backstories

Technically sessions should incorporate player backstories and personal goals, but it’s really hard to remember. I can never memorize every detail and seamlessly weave them into the narrative. Instead of expecting extensive prep work, the game itself should provide ways to make this process intuitive.

Here are some simple methods to integrate player goals without overwhelming the GM:

Let Players Fill in the Blanks: When introducing an NPC, ask a player, “Who is this, and what’s your connection to them?” This allows backstories to emerge naturally.

Use Goal Lists: Games like Slug Buster or Heart have players list objectives—like saving a town or defeating a specific enemy—which gives the GM clear, actionable story beats to work with.

Be Specific About Desires: Instead of vague motivations like “I want to be a hero” or “I want revenge,” players should define what achieving that goal actually looks like.

One of the trickiest parts of storytelling in a TTRPG is handling long-term player goals, and Brandon Sanderson’s Promise/Progress/Payoff framework offers a view of how he does it in a Book format…so can we learn from this?

Promise: When a player declares, “I want revenge,” that’s a narrative promise. The game is now telling that player, “This will be part of your story.” (potentially the culmination of your tale)

Payoff: The moment they finally get their chance—the big showdown, the climactic choice, the resolution—so technically this should come at the end of the adventure/campaign, unless you decide a that players will have new Promises every so often (mini-character arcs).

Progress: This is the hardest part. How do you make sure that goal doesn’t just sit there until the payoff?

In a book, progress might look like:

Leveling up and gaining the skills for the final fight.

Taking out a minion or rival along the way.

Finding hints about the antagonist’s whereabouts.

Discovering a key item or ally that will be crucial later.

As a GM, I don’t want to force a specific path, but I want to drop in these stepping stones naturally. The approaches mentioned earlier—asking players to define connections, using goal lists, or letting them shape key story moments— hopefully can all help keep these personal arcs alive without overloading my prep.

By making these mechanics explicit, the game can feel more personal and immersive, without putting all the weight on the GM’s shoulders.

Varying Encounter Starting Positions

How players start in an encounter dramatically changes its tactical flow. I’ve considered using these three starting conditions to adjust difficulty and narrative tone:

Positive Start: The players have an advantage—they get an ambush, hold a fortified position, benefit from clear sightlines, or have extra preparation time.

Neutral Start: Both sides begin on equal footing, with standard terrain, visibility, and weather.

Negative Start: The players begin at a disadvantage—caught off guard, in dim lighting, without cover, in a disadvantageous position, or facing a strong opening attack.

Changing starting conditions keeps encounters dynamic and prevents them from feeling repetitive. I’m hoping that previous encounters in the module format can define the starting position of the next encounter in line.

Designing EPIC Encounters: Keeping Combat Engaging and Dynamic

A great combat encounter is more than just throwing enemies at the players—it should entice, apply pressure, encourage interaction, and deliver consequences. This framework, often called EPIC Encounter Design, helps shape fights that feel strategic, cinematic, and memorable. I first saw this in one of Kelsey Dionne’s videos.

E – Enticement (Why Engage?)

Before combat even begins, players should have a reason to care. Maybe there’s a clear reward, a personal stake, or an environmental threat forcing them into the fight. Good enticement can include:

A powerful foe blocking their path forward towards what they need.

A moral dilemma, like saving hostages or stopping a ritual.

A battlefield opportunity, such as controlling a siege weapon or triggering a trap.

P – Pressure (The Stakes and Time Crunch)

Fights are more exciting when players feel like they need to act fast. Ways to increase a sense of urgency include:

Timers: Utilize both macro (session-wide) and micro (encounter-specific) timers to impose deadlines and prompt swift decision-making.

Resource Management: Design scenarios where resources are limited, compelling players to strategize and prioritize actions.

Escalating Consequences: Introduce stakes that heighten over time, motivating players to act promptly to prevent undesirable outcomes.

I – Interaction (More Than Just Rolling to Hit)

Players should have tactical options beyond just trading attacks. Good encounter design gives them:

Tactical positioning choices.

Objects to interact with, like levers, barricades, or unstable terrain.

Multiple victory conditions, which we will cover in more detail below.

C – Consequence (The Lasting Impact)

Every fight should change something. Even if players win, the battle might leave scars:

The enemy escapes and now knows their tactics.

An NPC ally dies in the chaos.

They burned resources they’ll need for the next challenge.

This ties back to the idea of Encounter Starting positions as well, mentioned above.

Pressure in EPIC - Expanding on it

Tension is key to an engaging one-shot, and timers and disruptions can push players to act without making them feel railroaded. I first started using timers after reading Index Card RPG. In addition to that, he mentions a couple other pacing mechanics.

Disruptions: Periodic hazards that interfere with progress (e.g., vines that entangle, shifting platforms, arcane pulses, or sudden gusts of wind).

Duration: A fixed timer at which point the encounter ends—whether or not players have succeeded. Examples include:

A giant door slamming shut, sealing off an escape.

A collapsing floor forcing immediate action.

A dragon awakening after three rounds.

By combining both disruption and duration mechanics, you can create encounters that force players to think fast without making them feel like they’re on a linear track.

Interaction in EPIC - Expanding on it

Encouraging Player Creativity with Multiple Win Conditions

One of the most effective ways to enhance player agency is by designing encounters with more than one way to succeed. Players should feel like they have options beyond simply defeating all enemies.

Here are some different types of win conditions to consider:

Combat-Based: Defeat all enemies, slay a key antagonist, or survive for a set number of rounds.

Objective-Based: Retrieve a special item, protect an NPC, disable a magical barrier, or uncover a hidden secret.

Time-Based: Escape a hazardous area before time runs out, prevent or complete a ritual, or hold a position for a specific number of turns.

Social & Tactical: Convince opponents to surrender, negotiate a peaceful resolution, infiltrate an area stealthily, or create a diversion.

By incorporating multiple victory paths within a single encounter, you provide players with tactical and narrative choices that can make them feel clever, and engaged.

Additionally, designing encounters with both primary and secondary objectives encourages creative problem-solving. For example, instead of simply “defeat the boss,” players could choose between destroying a magical artifact that weakens them, negotiating a truce, or holding out until reinforcements arrive.

Setting clear win conditions at the start of an encounter—and outlining the stakes for each—helps players make tactical decisions. Ideally, they should feel like all options remain viable throughout the encounter, rather than being locked into a single path from the start, like a board game.

For example, defeating the boss might be a straightforward victory, but if the players choose to stop the ritual instead, they might still succeed—just with lingering consequences, like the boss escaping or some residual magical effect.

Enemy Roles and Tactical Positioning

Where enemies are placed and how they function in a fight determines the flow of battle. A good mix of enemy types forces players to think beyond “who do I hit first?”

Vanguard – The Frontline Threat

These are the aggressive, in-your-face enemies that rush in to engage players immediately. They often have:

High health and armor to soak damage.

Abilities that punish disengagement.

Area denial mechanics (grapples, shockwaves, etc.).

Midguard – The Tactical Core

These enemies stay within the main fight, supporting vanguards and disrupting players. Their key traits:

Versatile abilities, like battlefield control or debuffs.

Mobility to shift between offense and defense.

Mid-range attacks or spells.

Rearguard – The Artillery

Positioned far from the fight, rearguards deal heavy damage from a distance but crumble if reached. They:

Rely on vanguards and midguards for protection.

Have powerful ranged attacks or area spells.

May reposition constantly to stay safe.

Reinforcements – The Surprise Element

These enemies arrive mid-fight, shifting the encounter's balance. They might:

Enter from a side passage or hidden location.

Arrive as a result of a failed objective.

Bring a new combat mechanic (like healing the boss).

I think that this video is a fantastic resource for this sort of tactical combat. I also think about monster roles that you find in games like 4th Edition D&D and Draw Steel.

However, I’m also loving the idea of minimizing bloat for monsters. I think that you can build in the feel of Vanguard/Midguard/Rearguard into Tactics tables like you see in Crown & Skull and Dragonbane. This is my hope for my own game.

Designing Dynamic Encounter Spaces

Encounters aren’t just about what happens in them—they’re about where they happen. The layout and terrain of a battlefield can significantly affect player decision-making. Borrowing from Index Card RPG, here are several room types that add tactical variety:

Barrier Room: An object (magical field, collapsed debris, arcane wall) blocks progress until it is removed.

Detangle Room: Players must avoid hazards (tendrils, shifting terrain, wild magic) that actively pull them in.

Locked Room: Requires finding a key—physical, magical, or narrative (e.g., defeating an enemy or solving a puzzle).

Kite Room: Players must keep moving to avoid a slow but persistent threat (e.g., a pursuing monster or spreading fire).

Pinch Room: A narrow area forces players into a choke point, favoring defense or area-based attacks.

Ambush Room: Enemies strike unexpectedly, catching players in a vulnerable position.

Siege Room: Players must defend a location from incoming threats or assault a fortified stronghold.

Tightrope Room: Players navigate a precarious or dangerous pathway, avoiding falls or hazards.

Duel Room: One player faces off against a powerful enemy in a one-on-one battle.

By varying encounter spaces throughout your one-shot, you ensure that each challenge feels distinct and presents new tactical dilemmas.

Now we have an encounter with multiple win conditions, a dynamic environment, and dynamic monsters….but is this sounding like a nightmare to run? Can we maintain all the VIBES of this sort of encounter but have it be simple and easy to manage? We’ll get to that after we finish off the One-Shot concepts.

Narrative & Player-Driven Solutions

Great one-shots don’t just rely on mechanics—they also embrace player creativity. To encourage player-driven storytelling, try these techniques:

Let Players Contribute to the Story: When introducing an NPC, ask the players how their character knows them. This fosters immediate investment in the world.

Similar to the backstory section of Letting Players fill in the blanks.

I like how Blades in the Dark does this subtly with gear or flashbacks.

Support Unconventional Ideas: If a player proposes a creative solution, support it by applying mechanics rather than shutting it down. (be a YES GM).

Keep Objectives Clear, but Solutions Open-Ended: Players should always know what success looks like, but they should have room to determine how they achieve it.

For example, if the goal is to prevent a cult ritual, the players might:

Defeat the cultists.

Disrupt the ritual by destroying key artifacts.

Trick the cult into believing their god has already arrived.

Seal off the location to trap the magic inside.

This almost flies in the face of stating the multiple win conditions at the start of an encounter. Will that limit a players potential? Maybe, maybe not. We’ll have to play around with it.

Drafting the Blueprint

I've gathered extensive notes on encounter design, storytelling, and plot development—but organizing and making sense of it all was its own challenge. I’ve even created videos on the topic along the way.

Honestly, at times, it felt like mental procrastination—more like a researcher endlessly gathering information rather than distilling it into practical, usable insights.

Streamlining Assistance

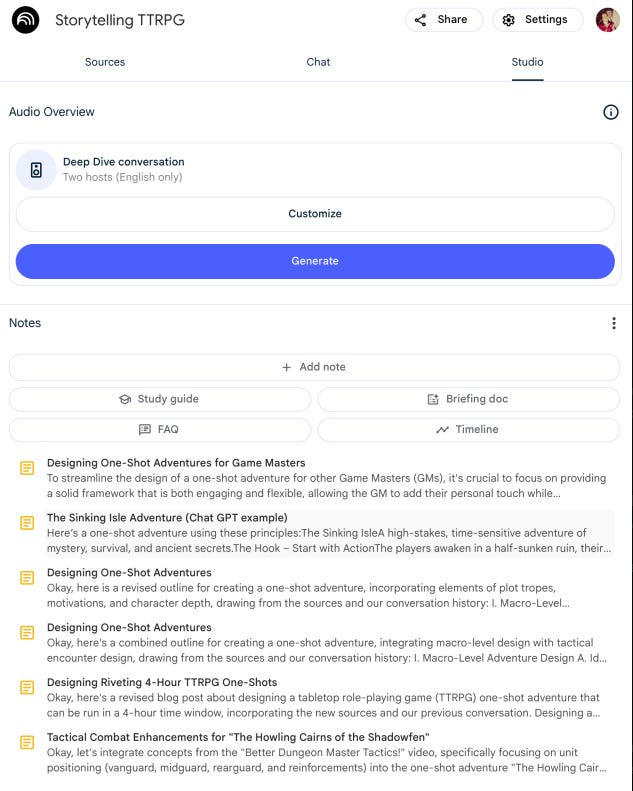

So, I decided to give Google Notebook a try to help me organize everything. Below, you'll see two images: the first shows the various resources I pulled in—my personal notes and some favorite YouTube videos—while the second captures the refined notes I compiled from that information.

Rewriting and Synthesizing Insights

Afterward, I went through the information Google Notebook gave me, and it was really fascinating to see it all organized. I then took my own personal notes based on that summarized info. Here's a quick breakdown of what I noted:

Encounter intro needs to have visual details that draw you in

Start with Fight, Chase, Puzzle, or Discovery

Initial One-Shot roll need to have this as part of the immediate beginning

Have a Cold Open

Immediately Hook - sense of curiosity

curiosity comes from immediate change, or information gaps

should an entire plot actually be written out? as an example?

Plot Types: Procedural, Mystery, Heist

coordinate the team/build the team

the rescue

get to the place

build the thing

the chase

the escape

get revenge

The heist, or bash & grab

The Con?

Whodunit

Solve the crime

Discover the world

Prophecy plot

Monster/Kaiju/Disaster

Frankenstein's Dilemma

Survive the Onslaught

Expose the Lie

Can always consider a McGuffin to add in? Something needed for the Procedural Plot

Quick Backstory

Time Element

Macro vs Micro

Macro for an One-shot, micro for an encounter

6-8 Encounters, each roughly 30min in scope: 4 hour session

EPIC Encounter design

Enticement - what’s the motivation/appeal

Pressure - sense of urgency

Interaction - meaningful choices

Consequences - success/failure outcomes

Room design - ICRPG styles?

entrance/interaction/trick-setback/climax/revelation

Cadence-Based design - different encounter types that are different strength based (Fighter, Thief, Wizard, Priest, etc)

Sensory details, dynamic environments, interesting objects

Encounter Hooks - draw in, description, promise, etc

Multi-solution encounters

multi-route, not tracks

Encounters are based on plot structure

promise of motion, conflict, change

Plot Turn 1 - Call to Action - Cold Open - Docking Roll

Pinch 1, Midpoint, Pinch 2, Plot turn 2, Resolution - too much like a book…get module

If mystery have a 3-clue rule (Alexandrian)

write down revelations, 3 clues to avoid chokepoints

Pass/Fail state for the Adventure for the entire One-shot

links to future One-shots and scenarios

Character driven

talkers, motivations

One-Shot tone promises - promise the tone immediately

Inversion of Character tropes? - too book like

Player Characters are the core of the story, not the campaign

Every character should feel like the main character

Understand what the players want - NPCs should engage that

Payoffs

NPCs

Likability, proactivity, competence?

Make them relatable

Sense of can’t have what they want? Flaws, limitations, handicaps

Theory of control - how do they try to control situations when things get shitty

Discrepancy between how they want others to see them and how they are privately

Scrap all the above…just make Talkers and give them a motivation and quirk.

Cleverness tips

Plot - Three Clue Rule

Multiple paths to success (at least 3)

List the 3 ways you’d like them to succeed, and then what are the clues that would lead to those resolutions?

Be blatant and intentional with your clue placement

How’s this Gonna Look?

Breaking Down a Book into Manageable Modules

In a traditional One-Shot, the Game Master is given everything they need to run the adventure. Think of classic 5e D&D modules like Lost Mine of Phandelver, where every encounter, monster, and building is fully detailed on each page. It’s all in there, no questions asked. But that’s not quite the approach I’m taking. I’m not designing a standalone One-Shot—rather, I’m building an entire game system book that includes multiple One-Shots within it. This allows me to focus more on the flavor and essence of each One-Shot, while not having to flush out each encounter of the One-shot, but providing resources to help generate them.

For example, let’s say the One-Shot revolves around taking down a big bad boss. In the One-Shot itself, I might outline the basic structure of six key module encounters, providing a win condition for each and naming the types of monsters you’d face. But in a different chapter, I could include tons of resources, like rolling tables and extra details, that allow the GM to customize things further—offering different win conditions, adding time pressures, introducing other monster types, and more. This approach not only lightens the load for writing the One-Shot (for me!), but it also grants the GM the freedom to adapt and create their own version of the adventure, making it feel more personalized and dynamic.

Simplified One-Shot Information

So, what will I need for my One-Shots?

First, I'll need an engaging intro that sets the stage with a Call to Action (procedural plot)—something that kicks off the adventure and draws players in. This will be followed by the Cold Open encounter, which introduces immediate action and sets the tone. Then, I’ll need a series of Talkers—characters the GM can use, each with their own motivations, quirks, and thematic ties to the One-Shot.

Next, I'll outline six module encounters, each with evocative locations and detailed descriptions of what's happening there. These encounters will be connected to the overall procedural plot, with at least one win condition for each. There may also be a consequence or a new starting point if a failure occurs, driving the story forward.

Finally, there will be a climactic, fully fleshed-out final encounter—no randomization here. It will be a well-defined, satisfying conclusion to the One-Shot. And of course, I'll need to define rewards and outcomes for different levels of success: full success, partial success, or failure, ensuring the players’ choices have meaningful consequences.

This is a great start for basic One-Shots….however, in addition to the core elements, my setting has a few unique features that I’ll need to include.

For starters, before the adventure begins, players will make an initial roll that determines the Cold Open. There will be four possible outcomes—positive, super positive, negative, or super negative—each setting the stage in a different way.

I'll also need a list of potential conditions that might arise during the One-Shot, as well as a selection of specific monsters. If the GM wants to randomize encounters, this will provide them with some options to mix things up.

Lastly, I love including Keywords—descriptive terms that the GM can use to enhance the tone and atmosphere of the session. These words can help set the mood and bring the environment to life. For example, if the setting is a lush waterfall jungle, some useful keywords might be "lush," "cascading," "humid," "vibrant," "verdant," "spiritual," "precarious," "harmonious," "mysterious," and "aquatic." These keywords will give the GM extra tools to immerse players in the world.

Potential Example

(coming soon 🤣.....look back over the next couple days and I should have one in here)

Final Thoughts

By combining varied win conditions, tactical room design, pacing mechanics, and player-driven storytelling, you create a flexible yet structured one-shot that encourages creativity while maintaining focus. By taking all of these encounter designs and making them quickly module in nature, it hopefully unweights the Game Master’s prep work.

Players should always feel like they have multiple paths to success, with high-stakes choices that meaningfully impact the outcome. Whether they win through strategy, combat, social maneuvering, or clever problem-solving, the best one-shots ensure that the journey is as memorable and a badass experience!

Now, go build something awesome 🤘!